Using the UConn HPC cluster

Up to the Phylogenetics main page

The UConn High Performance Computing facility on the Storrs campus is located in the lower level of the Gant Building. We will use this cluster for most of the data crunching we will do in this course. By now, you should have an account on the cluster, and today you will learn how to start analyses remotely (i.e. from your laptop), check on their status, and download the results when your analysis is finished.

Obtaining an account on the cluster

Before the course begins, fill out this form to get an account on the cluster (I’m assuming you don’t already have an account). You will need to sign in with your NetID to even get to the form. Everything should be straightforward except for perhaps the field Software Needed. Just leave this field blank, or enter something like “ssh, git, tar, bash” because we will definitely be using those programs.

Obtaining the necessary communications software

You will be using a couple of simple (and free) programs to communicate with the head node of the cluster. What programs you use depends upon whether you are going to be using Windows or MacOS.

If you use Windows

The program Git for Windows provides a terminal that will allow you to communicate with the cluster using a protocol known as SSH (Secure Shell). We will not actually use the “git” part of “Git for Windows”, although it is there in case you need it later. Instead, you will use the Git for Windows program bash to send commands to the cluster and see the output generated.

Visit the Git for Windows web site, press the Download button, and install Git for Windows on your system. Once installed, open Git BASH from the All Programs section of the start menu. This will open a terminal running the bash shell (a shell is a program that interprets operating system control commands) on your desktop.

If you use Mac

Start by opening the Terminal application, which you can find using the Finder main menu in Go > Applications > Utilities. You may wish to install iTerm2, which is a terminal program that makes some things easier than Terminal, but the built-in Terminal will work just fine for today.

Setting up SSH

Visit the Setting up an ssh alias page to create an alias for the HPC cluster. This will make logging in much easier. The process is somewhat tedious, but saves a lot of time and tedium in the future. The instructions below assume you have done at least steps 1-5 in those instructions.

Using SSH

The program ssh will allow you to communicate with the cluster using a protocol known as SSH (Secure Shell). You will use ssh to send commands to the cluster and see the output generated.

Type the following command into your terminal window:

ssh hpc

If this doesn’t work, there are a couple of possible reasons:

- Perhaps you skipped something when working through the Setting up an ssh alias page? The

hpcpart is an alias for the Storrs HPC cluster, so if that alias was not created, thenssh hpcwill not work; - Perhaps you are not on campus? If you are trying this at home and the terminal just hangs after you type

ssh hpcand hit return, you will need to login to the VPN (Virtual Private Network) so that you appear to be on campus. See the ITS Services VPN page for how to set this up.

SCP and Cyberduck

An SCP client is needed to to transfer files back and forth using the Secure Copy Protocol (SCP). I will show you how to transfer files using both methods, but for now you should go ahead and install Cyberduck. Cyberduck provides a nice graphical user interface, but you might find that the scp command line client lets you get your work done faster once you get used to using it.

Learning enough UNIX to get around

I’m presuming that you do not know a lot of UNIX commands, but, even if you are already a UNIX guru, please complete this section anyway because otherwise you will fail to create some files you will need later.

ls: finding out what is in the present working directory

The ls command lists the files in the present working directory. Try typing just

ls

If you need more details about files than you see here, type

ls -la

instead. This version provides information about file permissions, ownership, size, and last modification date.

pwd: finding out what directory you are in

Typing

pwd

shows you the full path of the present working directory. The path shown should end with your username, indicating that you are currently in your home directory.

mkdir: creating a new directory

Typing the following command will create a new directory named pauprun in your home directory:

mkdir pauprun

Use the ls command now to make sure a directory of that name was indeed created.

cd: leaving the nest and returning home again

The cd command lets you change the present working directory. To move into the newly-created pauprun directory, type

cd pauprun

You can always go back to your home directory (no matter how lost you get!) by typing just cd by itself

cd

If you want to go down one directory level (say from pauprun back down to your home directory), you can specify the parent directory using two dots:

cd ..

Finally, if you instead want to go back to the directory you were in before typing cd pauprun, you can type

cd -

nano: creating the run.nex file

One way to create a new file, or edit one that already exists, is to use the nano editor. You will now use nano to create a run.nex file containing a paup block. You will later execute this file in PAUP* to perform an analysis.

First use the pwd command to see where you are, then use cd to go into the pauprun directory if you are not already there. Type

nano run.nex

This will open the nano editor, and it should say [ New File ] at the bottom of the window to indicate that the run.nex file does not already exist. Note the menu of the commands along the bottom two rows. Each of these commands is invoked using the Ctrl key with the letter indicated. Thus, ^X Exit indicates that you can use the Ctrl key in combination with the letter X to exit nano.

For now, type the following into the editor:

#nexus

begin paup;

log file=algae.output.txt start replace flush;

execute algae.nex;

set criterion=likelihood autoclose;

lset nst=2 basefreq=estimate tratio=estimate rates=gamma shape=estimate;

hsearch swap=none start=stepwise addseq=random nrep=1;

lscores 1;

lset basefreq=previous tratio=previous shape=previous;

hsearch swap=tbr start=1;

savetrees file=algae.ml.tre brlens;

log stop;

quit;

end;

Once you have entered everything, use ^X to exit. Nano will ask if you want to save the modified buffer (a buffer is a predefined amount of computer memory used to store the text you type; the text stored in the buffer will be lost once you exit the program unless you save it to a file on the hard drive), at which point you should press the Y key to answer yes. Nano will now ask you whether you want to use the file name run.nex; this time just press the enter/return key to accept. Nano should now exit and you can use cat to look at the contents of the file you just created:

cat run.nex

Important when you use the cat command, be sure to specify a file name, otherwise cat will hang, expecting you to type something. That is, don’t type cat and then hit return. If you do get stuck and cat is waiting for you, you can get out of it by typing Ctrl-D.

Create the gopaup file

Now use nano to create a second file named gopaup in your pauprun directory. To do this, type pwd to make sure you are in the pauprun directory, then type nano gopaup. This file should contain this text:

#!/bin/bash

#SBATCH --partition=general

#SBATCH --qos=general

#SBATCH --job-name=pauprun

#SBATCH --mail-type=END

#SBATCH --mail-user=your.email@uconn.edu

cd $HOME/pauprun

paup -n run.nex

You may not wish to use the lines that begin with #SBATCH --mail-type= and #SBATCH --mail-user=. If you don’t want email notifications cluttering your email inbox, just delete these lines from the file (they are not required).

If you do use them, be sure to use your own email address and not your.email@uconn.edu!

Note that other mail options besides END are possible, including NONE, BEGIN, FAIL, and ALL. You can combine two or more in one line by separating them with commas:

#SBATCH --mail-type=END,FAIL

For the complete list of mail type options, see the SBATCH manual.

Getting files onto the cluster

The next three sections describe three different ways to get a file into a directory on the cluster. If the file is located on a website, which is the usual case for labs in this course, I would use the curl method. If you don’t like that method, or if the file you need to transfer is located on your local computer and not a web site, the other two sections offer alternative ways (both of which involve first getting the file onto your local computer, then uploading it to the cluster).

Using curl to download the algae.nex data file to the cluster directly

One of my favorite methods to transfer files that are stored on a web site involves the program curl (which stands for copy url). The following command should be carried out in a terminal that is already logged into the cluster.

In your terminal, navigate to the directory where you want to save the file (on the cluster). Use this command to download the algae.nex file directly into the present working directory on the cluster:

curl -Ok https://gnetum.eeb.uconn.edu/courses/phylogenetics/lab/algae.nex

The -O tells curl to save it under the same file name (algae.nex) that it has on the remote server. If you forget the -O, curl will just spit out the entire contents of the file to your terminal, which is almost never what you want!

The k in -Ok tells curl to go ahead even if it does not recognize the security certificate issued by the server.

If this method worked, skip now to the section A few more UNIX commands

Using Cyberduck to upload the algae.nex data file

(You can skip this section if the curl command worked for you.)

Download the file algae.nex and save it on your hard drive.

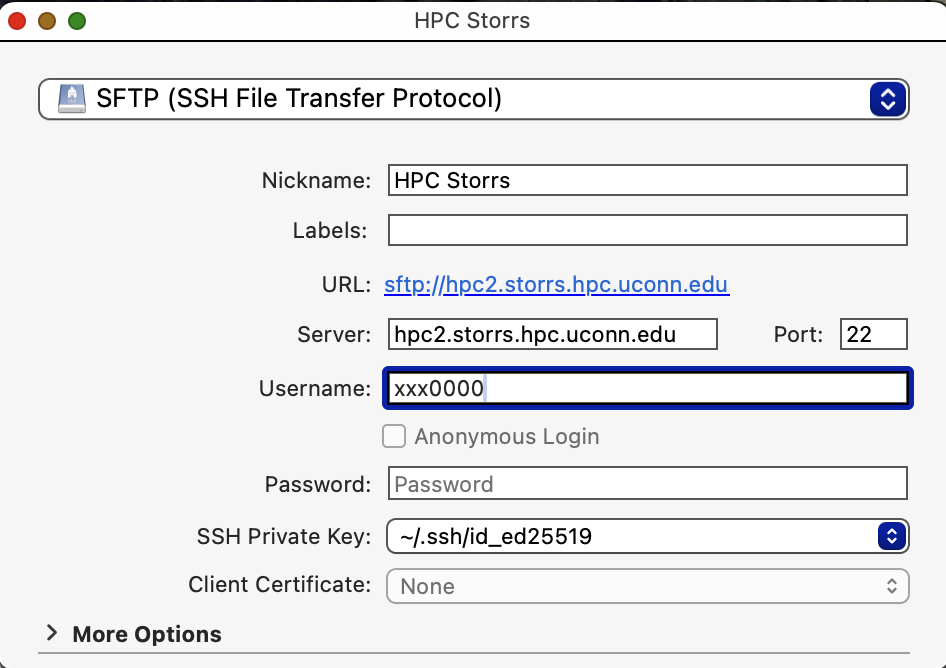

Open Cyberduck, choose Bookmark > New Bookmark from the main menu, then fill out the resulting dialog box as shown on the right (except substitute your own user name, of course). Be sure to change the protocol to SFTP (not the default FTP). Click the button to close the dialog box and you should see your bookmark appear at the bottom of the main window. Double click the bookmark to open a connection. You will then be warned that the host key is unknown - choose Allow (and go ahead and check the Always button so you do not need to do this every time.

Once you are in, you will see a listing of the files in your home directory on the cluster. To copy the algae.nex file to the cluster, you need only drag-and-drop it onto the Cyberduck window.

If this method worked, skip now to the section A few more UNIX commands

Using scp to upload the algae.nex data file

(You can skip this section if either the curl command or Cyberduck worked for you.)

Download the file algae.nex and save it on your hard drive.

The following should be carried out in a terminal that is logged in only to your local laptop (i.e. not logged into the remote cluster).

In your terminal, navigate to where you saved the file (on your local Mac or Windows computer). If you saved it on the desktop, you can go there by typing cd Desktop.

If you’ve made a shortcut in your .ssh/config file, you can use the following command to upload the algae.nex file to the cluster:

scp algae.nex hpc:

Don’t overlook the colon on the very end of the line! The hpc: part says that algae.nex should be moved to the cluster and the colon : separates the remote machine (hpc) from the directory where it is to be stored on the remote machine. If there is nothing after the colon, then the file is stored in your home directory on the remote machine.

A few more UNIX commands

You have now transferred a data file (algae.nex) to the cluster, but it may not be in the right place. Use the pwd and cd commands to ensure that you are in the pauprun directory, then type ls to see if the algae.nex file is there. The run.nex file contains a line containing the command execute algae.nex, which means that algae.nex should also be located in the pauprun directory.

mv: moving or renaming a file

If algae.nex is in your home directory, you can use the mv command to move it to the directory pauprun:

cd

mv algae.nex pauprun

The mv command takes two arguments. The first argument is the name of the directory or file you want to move, whereas the second argument is the destination. The destination could be either a directory (which is true in this case) or a file name. If the directory pauprun did not already exist, mv would have interpreted this as a request to rename algae.nex to the file name pauprun! So, be aware that mv can rename files as well as move them.

cp: copying a file

The cp command copies files. It leaves the original file in place and makes a copy elsewhere. You could have used this command to make a copy of algae.nex in the directory pauprun:

cp algae.nex pauprun

This would have left the original in your home directory, and made a duplicate of this file in the directory pauprun.

rm: cleaning up

The rm command removes files. If you had used the cp command to copy algae.nex into the pauprun directory, you could remove the original file using these commands:

cd

rm algae.nex

The first cd command just ensures that the copy you are removing will be the one in your home directory. The variable $HOME holds the path to your home directory. The symbol ~ is shorthand for $HOME. Typing cd by itself, cd ~, or cd $HOME all change the present working directory to $HOME.

To delete an entire directory (don’t try this now!), you can add the -rf flags. The r flag tells rm to recursively apply the remove command to everything in every subdirectory, while the f flag means force (don’t ask whether each file should be deleted in each subdirectory, just do it!):

rm -rf pauprun

The above command would remove everything in the pauprun directory (without asking!), and then remove the pauprun directory itself. I want to stress that rm -rf is a particularly dangerous command, so make sure you are not distracted or sleep-deprived when you use it! Unlike the Windows or Mac graphical user interface, files deleted using rm are not moved to the Recycle Bin or Trash, they are just gone. There is no undo for the rm command.

Installing PAUP*

The phylogeny program we will use today is called PAUP. PAUP is among the first phylogenetic analysis programs produced (1980s), and its developer (David L. Swofford) is still very actively adding to it today. The name PAUP is an acronym that originally stood for Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony. The asterisk was added once PAUP began incorporating likelihood and distance methods in the mid 1990s. PAUP can also be interpreted as a recursive acronym: Phylogenetic Analysis Using PAUP.

To install PAUP*, visit the download page and, in the section Command-line binaries, copy the link to the Centos/RedHat 64-bit version.

After logging into the cluster, type

curl -Ok https://phylosolutions.com/paup-test/paup4a168_centos64.gz

where the part after curl -Ok is the link that you copied. This will deposit a file named paup4a168_centos64.gz into your home directory. The .gz on the end of the filename indicates that this file has been compressed using the gzip program.

Next, you need to uncompress this file using the program gunzip:

gunzip paup4a168_centos64.gz

Now you should see (using ls) a file named paup4a168_centos64 in your home directory. The gunzip program uncompressed the file and removed the .gz file name extension.

Finally, you need to make the resulting file executable. To do this, use the chmod (change mode) command:

chmod +x paup4a168_centos64

You should now be able to start PAUP* by typing:

./paup4a168_centos64

The initial ./ is necessary because the Linux operating system does not look for executable programs in the current directory. Normally executable programs are located in certain directories (e.g. /usr/local/bin). Adding the initial period followed by a slash specifies that the program is located in the current directory (.).

Creating your own bin directory

It is conventional for executable programs to be placed in a directory named bin. Create a bin directory inside your home directory like this:

cd

mkdir bin

Move the paup4a168_centos64 executable inside your bin directory by typing:

mv paup4a168_centos64 ~/bin

Edit your ~/.bash_profile file in nano and add the following two lines beneath the comment “User specific environment and startup programs”

PATH=$PATH:$HOME/bin

export PATH

What does this do? This sets the search path for executable files to the existing path ($PATH) and adds the bin directory you just created to that path (:$HOME/bin). Now, every time you log into the cluster, any files in your bin directory will be automatically findable by the system.

To test this, log out and then log back in and type (you should be able to use the Tab key to complete the filename after typing the first few letters):

paup4a168_centos64

PAUP* should start right up! No need to add the ./ before paup.

Let’s do one other thing to make starting PAUP* more convenient:

cd ~/bin

mv paup4a168_centos64 paup

This just renames the PAUP* executable file to something easier to type (paup).

Starting a PAUP* analysis

The next tutorial you will explore in lab today will introduce you to the software PAUP, but for now we will do a short analysis using PAUP just to demonstrate how to submit a job to the cluster. There are two ways to run analyses on the cluster:

- use

sbatchto submit a batch job - use

srunto start an interactive session

You would normally use the interactive session approach if you are just experimenting or are making sure that a program will start successfully. For a phylogenetic analysis that may take some time, you almost always want to submit it as a batch job (see below). The beauty of batch jobs is that you can close down your connection to the cluster and reconnect later (after the system sends you an email telling you that your run is finished).

If you’ve been following the directions in sequence, you now have three files (algae.nex, run.nex, and gopaup) in your $HOME/pauprun directory on the cluster. Use the pwd command to make sure you are in the $HOME/pauprun directory (use the cd command to get there if not), then the cat gopaup command to look at the contents of the gopaup file you created earlier. You should see the following:

#!/bin/bash

#SBATCH --partition=general

#SBATCH --qos=general

#SBATCH --job-name=pauprun

#SBATCH --mail-type=END

#SBATCH --mail-user=your.email@uconn.edu

cd $HOME/pauprun

paup -n run.nex

This file will be used by software called SLURM to start your run. SLURM provides a command called sbatch that you will use to submit your analysis. The SLURM sbatch command will look for a core (i.e. a processor) on a node (i.e. a machine) in the cluster that is currently not being used and will start your analysis on that node. This saves you the effort of looking amongst all nodes in the cluster for a core that is not busy.

Here is an explanation of each of the lines in gopaup:

- The 1st line specifies the command interpreter to use (just include this in your scripts verbatim).

- The 2nd through 6th lines begin with

#SBATCHand are interpreted as commands by SLURM itself. In this case, the first and second#SBATCHcommands tell SLURM to use the general partition (--partition=general) and the general quality of service (--qos=general). You should always include these two lines verbatim. The third#SBATCHline gives a name to your job (--job-name=pauprun). You could changepauprunhere to something else, but keep your job names short and without embedded spaces or punctuation. The job name will help you identify your run when checking status. The fourth and fifth#SBATCHline asks slurm to email you when the job is finished. - The 7th line is simply a

cdcommand that changes the present working directory to the pauprun directory you created earlier. This will ensure that anything saved by PAUP* ends up in this directory rather than in your home directory. - The 8th and last line starts up PAUP* and executes the run.nex file. The

-nflag tells PAUP* that no human is going to be listening or answering questions, so it should just use default answers to any questions it needs to ask during the run.

Submitting a job using sbatch

Now you are ready to start the analysis. Type these commands to start your run:

cd ~/pauprun

sbatch gopaup

(The cd ~/pauprun is there just to ensure that you are in the correct directory.)

Checking status using squeue

Note that the --mail command in your gopaup file will result in an email notification, but you can also see if your run is still going using the squeue command:

squeue

If it is running, you will see an entry named pauprun. Here is what it looked like for me:

$ squeue

JOBID PARTITION NAME USER ST TIME NODES NODELIST(REASON)

22138117 general pauprun pol02003 R 0:00:41 1 cn530

The R under ST (state) means that my job is running. This job goes so fast that you will be lucky to find it in the running state. If you see no jobs listed when you run squeue, it means your job has finished.

Killing a job using scancel

Sometimes it is clear that an analysis is not going to do what you wanted it to. Suppose that just after you press the Enter key to start an analysis, you realize that you forgot to put in a savetrees command in your paup block (so in the end you will not be able to see the results of the search). In such situations, you really want to just kill the job, fix the problem, and then start it up again. Use the scancel command for this. Note that in the output of the squeue command above, my run had a job-ID equal to 22138117. I could kill the job like this:

scancel 22138117

Be sure to delete any output files that have already been created before starting your run over again.

While PAUP* is running

While PAUP* is running, you can use cat to look at the log file:

cd pauprun

cat algae.output.txt

Using Cyberduck to download the log file and the tree file

When PAUP* finishes, squeue will no longer list your process. At this point, you need to use Cyberduck or scp to get the log and tree files that were saved back to your local computer. Assuming you left Cyberduck open and connected to the cluster, double-click on the pauprun directory and locate the files algae.ml.tre and algae.output.txt. Select these two files and drag them out of the Cyberduck window and drop them on your desktop. After a flurry of activity, Cyberduck should report that the two files were downloaded successfully, at which point you can close the download status window.

Using scp to download the log file and the tree file

You can also use scp to get the log and tree files that were saved back to your local computer, but, again, if you are happy with Cyberduck you can skip this section. In the console on your local laptop, type the following (being careful to separate the final dot character from everything else by a blank space):

scp hpc:pauprun/algae.output.txt .

scp hpc:pauprun/algae.ml.tre .

These scp commands copy the files algae.output.txt and algae.ml.tre to your current directory (this is what the single dot at the end of each line stands for).

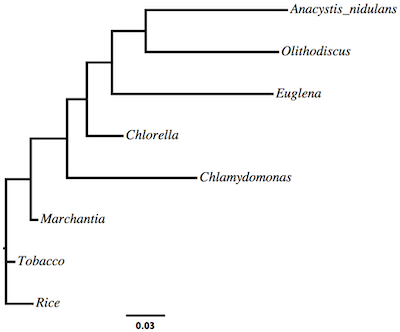

Using FigTree to view tree files

If you do not already have it, download and install the FigTree application on your laptop. FigTree is a Java application, so you will also need to install a Java Runtime Environment (JRE) if you don’t already have one (just start FigTree and it will tell you if it cannot find a JRE). Once FigTree is running, choose File > Open from the menu to open the algae.ml.tre file.

Adjusting taxon label font

The first thing you will probably want to do is make the taxon labels larger or change the font. Expand the Tip Labels section on the left and play with the Font Size up/down control. You can also set font details in the preferences, which will save you a lot of time in the future

Line thickness

You can modify the thickness of the lines used by FigTree to draw the edges of the tree by expanding the Appearance tab.

Ladderization

You can ladderize the tree (make it appear to flow one way or the other) by playing with the Order Nodes option in the Trees tab.

Export tree as PDF

There are many other options that you can discover in FigTree, but one more thing to try today is to save the tree as a PDF file. Once you have the tree looking just the way you want, choose File > Export PDF…

Why have PAUP* create the log file algae.output.txt?

In your pauprun directory, SLURM saved the output that PAUP* normally sends to the console to a file named something like slurm-645170.out (your file will have a different number, however). You will not need this file after the run: the log command in your paup block ends up saving the same output in the file algae.output.txt. Why did we tell PAUP* to start a log file if SGE was going to save the output anyway? The main reason is that you can view the log file during the run, but you cannot view slurm-645170.out until the run is finished. There may come a day when you have a PAUP* run that has been going for several days and want to know whether it is 10% or 90% finished. At this point you will appreciate being able to view the output file!

Delete the slurm-xxxx.out file using the rm command

Because you do not need the slurm-xxxxx.out file (where xxxx is a placeholder for the job number), delete it using the rm command (the -f stands for force; i.e. don’t ask if it is ok, just do it!):

cd

cd pauprun

rm -f slurm-*.out

You also no longer need the log and tree files because you downloaded them to your local computer using PSFTP:

rm -f algae.ml.tre

rm -f algae.output.txt

It is a good idea to delete files you no longer need for two reasons:

- you will later wonder whether you downloaded those files to your local machine and will have to spend time making sure you actually have saved the results locally

- our cluster only has so much disk space, and thus it is just not possible for everyone to keep every file they ever created

Tips and tricks

Here are some miscellaneous tips and tricks to make your life easier when communicating with the cluster.

Command completion using the tab key

You can often get away with only typing the first few letters of a filename; try pressing the Tab key after the first few letters and the command interpreter will try to complete the thought. For example, cd into the pauprun directory, then type

cat alg<TAB>

If algae.nex is the only file in the directory in which the first three letters are alg, then the command interpreter will type in the rest of the file name for you.

Wildcards

I’ve already mentioned this tip, but it bears repeating. When using most UNIX commands that accept filenames (e.g. ls, rm, mv, cp), you can place an asterisk inside the filename to stand in for any number of letters. So

ls algae*

will produce output like this

algae.ml.tre algae.nex algae.output.txt

Man pages

If you want to learn more options for any of the UNIX commands, you can use the man command to see the manual for that command. For example, here’s how to see the manual describing the ls command:

man ls

It is important to know how to escape from a man page! The way to get out is to type the letter q. You can page down using Ctrl-f, page up through a man page using Ctrl-b, go to the end using Shift-g and return to the very beginning using 1,Shift-g (that is, type a 1, release it, then type Shift-g). You can also move line by line in a man page using the down and up arrows, and page by page using the PgUp and PgDn keys.

HPC Storrs information

You can find a lot of great information about the Storrs HPC cluster at the About Storrs HPC web site.